by Kasey

We’ve had a busy season at the redoubt so far, but behind the scenes, the effort to package and transport the objects to their new stores is still ongoing. We’ve made a lot of progress! 93 boxes and counting (but hopefully not too much higher).

Not

only is it massive, it has hundreds of small, intricately and purposely placed

pieces attached to it. It also captures a definitive moment in history - for

both England, who achieved another victory in the Seven Years War, and New

France, which would become my home country of Canada. The battle began 13

September, 1759 on a plateau resting just outside what is now Quebec City.

Commanded by the young and charismatic General James Wolfe, the British forces had triumphed numerous times in a three month siege, culminating in this battle on the Plains of Abraham, itself lasting no more than 15 minutes and involving no more than 10 000 personnel.

By the 18thcentury, muskets had evolved into a fairly reliable combat weapon. Lead balls like these ones were the ammunition of choice because they could be loaded quickly. A musket shot on target was almost always fatal. Both generals died from musket shot wounds - Wolfe instantly, and Montcalm the next day, but not before he’d written his surrender to Wolfe, the cruel irony of which being that, unbeknownst to him, Wolfe fell within minutes of the battle starting.

The model, of course, is also an interesting object because it actually belongs to the Royal Sussex regiment - which, as aforementioned, fought in the battle the model depicts. According to regimental history, the 35th picked up the plumes of the fleeing French army and put them in their own caps. The plume became emblematic of the regiment's victory, being incorporated officially into the badge in 1881.

We’ve had a busy season at the redoubt so far, but behind the scenes, the effort to package and transport the objects to their new stores is still ongoing. We’ve made a lot of progress! 93 boxes and counting (but hopefully not too much higher).

As we come closer to fully clearing the store,

we’re faced again with some of the more challenging objects we had to put

off until we figured out how best to accommodate their needs.

Like this model of the Battle of Quebec . . .

|

| You can't see my face, but I assure you it expresses despair over how on earth we are supposed to move this |

|

To his superiors, Wolfe was startlingly fearless. When asked

if Wolfe was mad, King George II is supposedly to have said 'Mad is he? I hope he will bite some of my other generals' |

|

| Montcalm spent most of his time in Quebec being fed up with his superior, Governor de Vaudreuil, who very much underestimated Wolfe's resolve |

Commanded by the young and charismatic General James Wolfe, the British forces had triumphed numerous times in a three month siege, culminating in this battle on the Plains of Abraham, itself lasting no more than 15 minutes and involving no more than 10 000 personnel.

Most memorable perhaps is that both Wolfe, and the French

General, Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, lost their lives.

|

| 'The Death of General Wolfe' (1771) by Benjamin West. Initially exhibited at the Royal Academy, it was given to Canada in 1921 as a gesture of thanks for exceptional service during WWI |

Wolfe’s death is commemorated in a

painting that is as beautiful as it is famous, immortalizing his embodiment of English

ascendancy in the New World. Montcalm’s death was commemorated in a painting as well, and it’s . . . err,

alright?

|

| La Mort de Montcalm'(1902) by Marc Aurele de Foy Suzor Cote |

Let’s just say it doesn’t do justice to the exasperated general, who,

though not as renowned as his counterpart, still had his merits (Many thanks to Canadian historical cartoonist, Kate Beaton, for hilariously pointing this out).

As the 257th anniversary is only 2 weeks away, I was inspired to see what other objects we might have that pertain to this pivotal (and disproportionately short) battle. The first objects I came across were musket balls taken from the Plains of Abraham.

As the 257th anniversary is only 2 weeks away, I was inspired to see what other objects we might have that pertain to this pivotal (and disproportionately short) battle. The first objects I came across were musket balls taken from the Plains of Abraham.

|

| Musket balls taken from the Plains of Abraham |

By the 18thcentury, muskets had evolved into a fairly reliable combat weapon. Lead balls like these ones were the ammunition of choice because they could be loaded quickly. A musket shot on target was almost always fatal. Both generals died from musket shot wounds - Wolfe instantly, and Montcalm the next day, but not before he’d written his surrender to Wolfe, the cruel irony of which being that, unbeknownst to him, Wolfe fell within minutes of the battle starting.

|

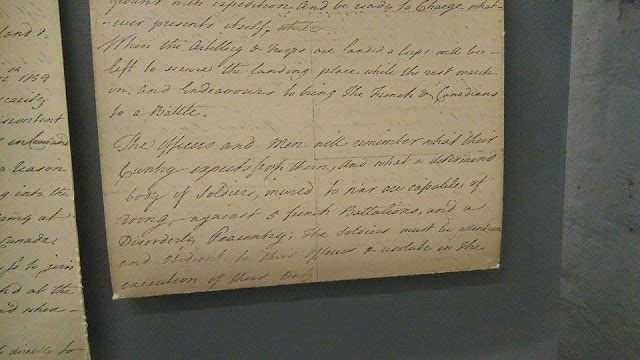

| Copy of Sir Henry Fletcher's letter |

We also have a copy of a letter (written on different days) by Sir Henry Fletcher, commanding officer of the 35th Regiment of Foot - which served under General Wolfe in Quebec, and which would later become the 1st Btn. of the Royal Sussex.

On 10 September, 1759, he writes confidently to his father, but is also cautious about prematurely celebrating an imminent surrender, expressing that the regiment 'still [had] a great deal of duty upon [their] hands.'

In the second part of the letter, dated 14 September, 1759, he mourns the loss of General Wolfe, saying he 'ought to be taking a moment to the memory of our general, who fell at the head of our first line.'

What's also quite special about this letter is that it contains a copy of General Wolfe's Orders, written kindly but with an implicit demand that the officers and men ''will remember what their country expects from them.'' Almost 50 years later, Admiral Nelson would say something similar moments before the Battle of Trafalgar. A remarkable parallel I think.

|

| Line from General Wolfe's orders |

If you have any ideas about how we might move this model from A to B, please feel free to get in touch!

Or maybe just wish us (a lot of) luck!

Or maybe just wish us (a lot of) luck!

Comments

Post a Comment